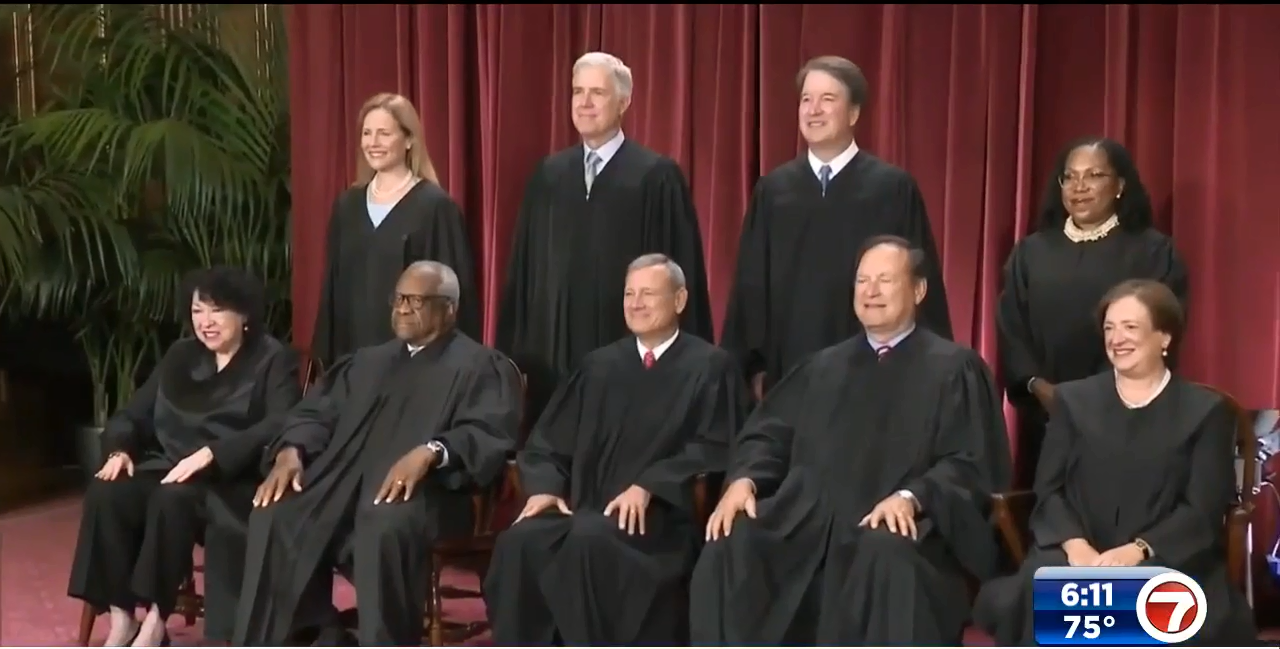

WASHINGTON (AP) — A Supreme Court that is the most diverse in history will hear two cases Monday challenging the use of affirmative action in higher education. It’s a topic a number of the justices have already said a lot about.

The cases say that Harvard University and the University of North Carolina — respectively the nation’s oldest private and oldest public college — improperly use race as a factor in admissions, giving preference to Black, Hispanic and Native American students. And the conservative-dominated court is widely expected to rule against the universities.

Three of the court’s six conservatives are on record opposing affirmative action policies while one of the court’s liberals has been a passionate defender. That could make for a particularly interesting argument, especially given the makeup of the court. The group of nine justices includes the first Hispanic justice as well as two justices who are Black — one liberal and one conservative — and who are expected to disagree on the case’s outcome.

What members of the court have said previously about affirmative action and what to watch for during Monday’s arguments:

CHIEF JUSTICE JOHN ROBERTS

In his 17 years leading the court Roberts has repeatedly opposed affirmative action policies and criticized race-based categorizations.

In a 2007 case in which the court rejected efforts to combat segregation in Seattle schools he wrote: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” And in a different case involving race in redistricting he memorably wrote: “It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race.”

The last time the court considered an affirmative action case, in 2015, Roberts asked about the benefits of diversity this way during arguments: “What unique perspective does a minority student bring to a physics class?”

CLARENCE THOMAS

Thomas has a long record of opposition to affirmative action programs, and his views relate to is own experience. The court’s second Black justice is also its most outspoken opponent of affirmative action and has said that his law degree from Yale was “tainted” because people assumed was admitted to the school because of affirmative action.

In 2003, Thomas dissented when the court, by a 5-4 vote, backed the use of race in admissions. He wrote in that case, Grutter v. Bollinger: “I believe Blacks can achieve in every avenue of American life without the meddling of university administrators.” Every time “the government places citizens on racial registers and makes relevant to the provision of burdens or benefits, it demeans us all.”

SAMUEL ALITO

Alito has made no secret of his disagreement with the court’s affirmative action rulings. In 2016 when the court upheld a University of Texas admissions program that takes account of race — a ruling surprising some observers — Alito wrote a dissent that was more than twice as long as the majority opinion. He also summarized his dissent out loud in court, a rare step justices take as a way of emphasizing their displeasure.

NEIL GORSUCH, BRETT KAVANAUGH, AMY CONEY BARRETT

The court’s remaining three conservatives, all appointed by President Donald Trump, have no track record on affirmative action. Of the three, however, Kavanaugh has underscored his commitment to diversity in his own hiring practices. During his Senate confirmation hearing he noted that a majority of the young lawyers he’s hired as law clerks have been women and more than a quarter have been minorities.

Still, at the time, groups pointed to a 1999 Wall Street Journal article Kavanaugh wrote as evidence he would oppose affirmative action. The article quoted conservative Justice Antonin Scalia to say that it’s a fundamental constitutional principle that “in the eyes of government, we are just one race here. It is American.”

SONIA SOTOMAYOR

The liberal Sotomayor has repeatedly and proudly said that she’s a “product of affirmative action.” The court’s first Hispanic justice grew up in the Bronx, New York, and attended Princeton on a full scholarship. She excelled and went on to Yale Law School. Affirmative action was a “door opener that changed the course of my life,” she has said.

On the court, Sotomayor has defended affirmative action, most strongly perhaps in a 2014 case in which her colleagues upheld a Michigan affirmative action ban passed in the wake of the court’s Grutter decision. “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination,” she wrote, pointedly paraphrasing Roberts.

ELENA KAGAN

Before becoming a Supreme Court justice, Kagan was dean of Harvard Law School and President Barack Obama’s top Supreme Court lawyer as solicitor general. She sat out earlier affirmative action cases at the court, likely because of her involvement in the cases while in government. The Obama administration took positions supporting affirmative action.

KETANJI BROWN JACKSON

Jackson, who earlier this year became the first Black woman to sit on the Supreme Court, could have a lot to say on the topic of affirmative action. While the group challenging Harvard’s and UNC’s policies argues that the Constitution is “colorblind,” Jackson said earlier this month in a different case that she believes constitutional amendments made following the Civil War were adopted in a race-conscious way.

Jackson will only participate in the UNC case. During her confirmation hearings earlier this year the liberal justice pledged to sit out the Harvard case because she was a member of the school’s board.

SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR

Yes, the court’s first female justice retired from the court nearly two decades ago. But her words are likely to echo at Monday’s arguments since she’s the author of the Grutter v. Bollinger opinion the justices are being asked to overturn. O’Connor closed that 2003 opinion in part by saying that affirmative action’s days might be numbered. She wrote: “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.”

If the court does bar race-conscious admissions when it decides the case by the middle of 2023, it would shave five years off her timeline.